Debtors in Accounting: Meaning, Examples & How They Work

Table of Contents

- What Are Debtors in Accounting?

- Debtor Meaning and Key Points

- Debtor Rights in Business and Finance

- Debtor Obligations and Responsibilities

- What Happens When a Debtor Doesn’t Pay?

- Penalties and Risks for Debtors

- Debtors vs Creditors Explained

- Is a Customer a Debtor?

- Are Debtors Assets on the Balance Sheet?

- Debtor Examples in Real Businesses

- How Businesses Manage Debtors and Collections

- Bank Debtors and Bank Creditors

- Laws That Protect Debtors

- Ready to take control of debtor balances and cash flow?

- FAQs about Debtors

A debtor is any person or business that owes money, goods, or services to another party (usually because they received value first and will pay later). In day-to-day accounting, “debtors” often show up as customers who haven’t paid an invoice yet. An important detail that affects cash flow, reporting, and collections.

This guide will cover:

- What debtors are in accounting and where they appear in your books

- Debtor rights, obligations, and what happens if payment doesn’t come in

- The difference between debtors and creditors

- How debtors affect your balance sheet, reporting, and collections process

- Best practices for managing customer payments and reducing late invoices

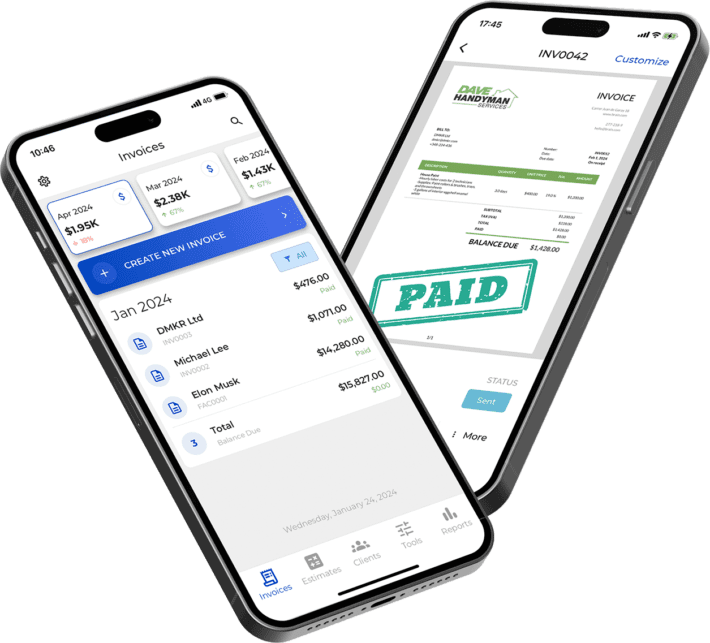

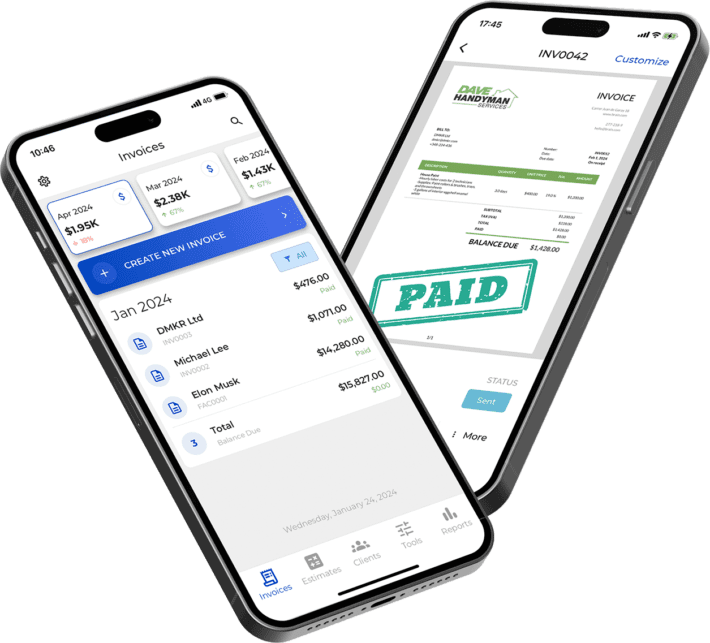

Before we get into the details: if you want to reduce confusion with customers and get paid faster, start with clear invoices from day one. Invoice Fly’s invoicing software helps you send professional invoices, track payment status, and follow up consistently—so fewer customer accounts drift into “overdue.”

What Are Debtors in Accounting?

In accounting, debtors are people or organizations that owe your business money because they’ve already received your goods or services but haven’t paid yet. This is most common when you offer payment terms like “Net 15” or “Net 30.”

Think of debtors as the unpaid sales side of your business—still valuable, but not cash in the bank. Debtors matter because they:

- Impact your cash flow (you can’t spend what you haven’t collected)

- Influence working capital and liquidity ratios

- Affect financial statements like the balance sheet and cash flow reporting

In most small businesses, debtors are tracked through accounts receivable and organized through a subsidiary ledger (customer-by-customer detail) that rolls up into your general ledger totals.

After you’ve created a clear billing process, good bookkeeping keeps your debtor balances from quietly piling up.

Get Started with Invoice Fly’s Software

Invoice Fly is a smart, fast, and easy-to-use invoicing software designed for freelancers, contractors, and small business owners. Create and send invoices, track payments, and manage your business — all in one place.

Debtor Meaning and Key Points

Here’s the simplest debtor meaning according to Cornell Law School: a debtor owes a debt.

In business accounting, a debtor typically exists when:

- You deliver a product or service

- You issue an invoice

- The customer hasn’t paid yet

A few practical points that matter for small businesses:

- Debtors increase when you make credit sales, and decrease when you collect payments.

- Strong invoice policies reduce late payments (clear terms, due dates, and follow-ups).

- The longer a balance stays unpaid, the higher the risk it becomes uncollectible.

Debtor Rights in Business and Finance

Debtors still have rights, even when they’re behind on payment. In the U.S., consumer debt collection is regulated, and certain communications and tactics are restricted.

In a business-to-business setting, rights and remedies can depend on:

- Your contract terms (payment schedule, late fees, dispute windows)

- State laws governing collections and commercial transactions

- Whether the debt is secured (collateral) or unsecured

If bankruptcy becomes part of the picture, “debtor” can also refer to the person or entity filing for relief under bankruptcy rules.

Debtor Obligations and Responsibilities

A debtor’s responsibilities usually start with the agreement they accepted—explicitly (signed contract) or implicitly (accepted quote/estimate and received the service).

Common obligations include:

- Paying the correct amount by the due date

- Following dispute procedures (if the invoice is contested)

- Communicating promptly if payment timing changes

- Complying with interest or late-fee terms if those were disclosed upfront

What Happens When a Debtor Doesn’t Pay?

When a debtor doesn’t pay, the “what now?” depends on your credit terms, your relationship with the customer, and the age and size of the balance.

A practical escalation path often looks like this:

- Reminder shortly after the due date (friendly tone, resend invoice)

- Second notice with a clear deadline and payment options

- Phone call to confirm receipt and resolve disputes

- Final notice stating next steps (pause services, late fees, collections)

- Collections or legal action if the amount and likelihood of recovery justify it

Accounting-wise, long-overdue balances may eventually be moved into a bad-debt process. Under accrual accounting, you may need a bad debt expense and allowance approach.

Penalties and Risks for Debtors

For debtors, the consequences of nonpayment can range from mild to severe depending on the setting:

- Late fees or interest (if permitted by contract and state law)

- Service interruption (common in recurring services or subscriptions)

- Damage to business credit (B2B payment history can affect access to trade credit)

- Collection efforts that add pressure and cost

- Legal action such as a demand letter, small claims, or civil suit

For your business, the risks are just as real:

- Uncollected invoices create cash crunches and missed opportunities

- Time spent chasing payments drains productivity

- High receivables can make your business look weaker to lenders

Debtors vs Creditors Explained

The easiest way to remember this:

- debtor vs creditor: debtor owes money; creditor receives money.

This also flips depending on whose books you’re looking at:

- On your books, a customer who hasn’t paid is a debtor.

- On the customer’s books, they record a payable and you are their creditor.

Is a Customer a Debtor?

Often, yes. A customer becomes a debtor the moment they receive goods/services on credit and haven’t paid yet.

In a small business context, it’s usually:

- A customer with an unpaid invoice

- A client on a payment plan

- A business account billed after delivery (common in contracting)

This distinction matters because it affects follow-up timing, customer communication, and the way you forecast incoming cash.

Are Debtors Assets on the Balance Sheet?

Yes, most of the time. Debtors are typically classified as current assets because they represent money you expect to receive within a year (often within 30–90 days).

In standard formats, debtors appear under:

- Current assets → Accounts receivable (trade receivables)

That said, not every receivable is equally valuable. Older balances may be harder to collect. Many businesses use an aging schedule to review:

- Current (not overdue)

- 1–30 days overdue

- 31–60 days overdue

- 61–90 days overdue

- 90+ days overdue

If you’re building a reporting stack, keeping your accounts organized is critical. A clean chart of accounts makes it easier to track receivables, deposits, sales, and write-offs without messy rework later.

Debtor Examples in Real Businesses

A clear debtor example helps connect the definition to daily operations:

- Plumber: Completes a repair and invoices the property manager with Net 30 terms. Until payment arrives, the property manager is the plumber’s debtor.

- Freelance designer: Delivers brand assets and invoices the client for the remaining 50% balance due in 15 days. The client is the debtor until the invoice is paid.

- Wholesale supplier: Ships inventory to a retail shop on trade credit. The retail shop is the debtor; the supplier records the amount as accounts receivable.

- Software agency: Bills milestones after delivery. Each unpaid milestone invoice creates a debtor balance until settled.

In each case, the debtor isn’t necessarily “bad”, they’re just unpaid. The goal is to keep that unpaid period short, predictable, and professionally managed.

How Businesses Manage Debtors and Collections

Managing debtors is mostly about preventing delays before they happen and responding quickly when they do.

Here are practical habits that work for many U.S. small businesses:

1) Use clear terms and consistent documentation

Make sure every invoice includes:

- Due date and terms (Net 15/30)

- Itemized scope and prices

- Payment methods and instructions

- Late fee policy (where allowed)

2) Standardize your follow-up schedule

A simple process usually beats an aggressive one. Example:

- Reminder at 3 days overdue

- Second reminder at 10 days overdue

- Call at 14 days overdue

- Final notice at 21 days overdue

3) Track debtor balances like a KPI

Even if you’re not doing advanced finance, watching receivables and overdue totals helps you avoid surprises. Many owners also monitor cash inflows and overhead together.

4) Know when to stop work

For service businesses, continuing work while invoices are overdue is a common way debt grows. Clear pause policies protect your time and reduce risk.

5) Escalate thoughtfully

If a customer is unresponsive and the amount is meaningful:

- Consider a demand letter

- Evaluate small claims options

- Use a reputable collection approach consistent with consumer protection rules (where applicable)

Bank Debtors and Bank Creditors

Banks use the same concepts, just at scale:

- If you take a business loan, you become the bank’s debtor.

- The bank becomes the creditor because it is owed repayment.

The “secured vs unsecured” piece matters here:

- Secured debt: backed by collateral (like equipment or property)

- Unsecured debt: not backed by collateral (often higher rates or stricter underwriting)

If you’re planning financing and want to model monthly payments before you borrow, a loan calculator can help you estimate repayment scenarios and avoid overcommitting cash flow.

Laws That Protect Debtors

In the U.S., debtor protections depend on whether the debt is consumer or commercial, and on federal and state rules.

If you’re collecting as a small business, it’s smart to:

- Keep communications professional and documented

- Avoid threats or misleading statements

- Follow your contract terms and applicable laws

- Escalate to legal help when amounts justify it

Ready to take control of debtor balances and cash flow?

At some point, every growing business needs a repeatable receivables workflow. The practical goal is simple: keep debtor balances visible, invoices clear, and follow-ups consistent—so you spend less time chasing payments and more time doing billable work.To simplify the process, use Invoice Fly’s invoicing software to send invoices with clear terms, track what’s overdue, and keep customer communication organized.

Get Started with Invoice Fly’s Software

Invoice Fly is a smart, fast, and easy-to-use invoicing software designed for freelancers, contractors, and small business owners. Create and send invoices, track payments, and manage your business — all in one place.

FAQs about Debtors

The debtor is the person or business that owes money. The creditor is the person or business that is owed money.

A customer is a debtor when they’ve received goods or services and haven’t paid yet. If they prepaid or have a credit balance, the roles can flip depending on the situation and the accounting treatment.

In the U.S., debtors have the right to fair and lawful treatment. This includes protection from harassment or misleading claims, the right to receive accurate information about the debt, the ability to dispute incorrect charges, and limits on when and how collectors can contact them. Consumer debts are protected by federal and state laws, while business debtor rights are usually defined by contract terms and commercial law.

Collectors can pursue repayment through legal channels, but they cannot use harassment or deceptive tactics.

Credit cards are usually unsecured debt, so there’s typically no direct collateral claim like a mortgage. However, if a creditor sues and gets a judgment, collection remedies can vary by state and circumstances.